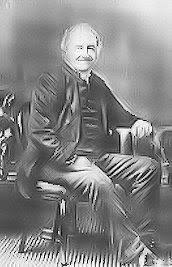

In 1739, prolific hymn writer Charles Wesley penned a Christmas hymn titled “Hark How All the Welkin Rings” for his and brother John’s collection, Hymns and Sacred Poems. The opening line referenced the “welkin,” an old English word for the sky or heavens, ringing with joyful praise for the newborn king. First published under the title “Hymn for Christmas Day”, the somber, sober tune paired with the hymn of 10 stanzas failed to gain much traction. Over the next decades, Wesley’s hymn underwent various tweaks and changes by other editors, much to the dismay of the protective Wesley brothers.Wesley, inspired by the sounds of London church bells while walking to church on Christmas Day, wrote the “Hark” poem about a year after his conversion to be read on Christmas Day.

In 1753, famed preacher George Whitefield reworked the first line to the familiar “Hark! the herald angels sing.” This marked a pivotal change in the carol’s evolution.

Beyond just replacing the archaic “welkin”, Whitefield’s adjustment shifted the perspective. Wesley’s initial focus was heaven’s chorus glorifying the newborn king. Whitefield reframed it to imagine humanity joining the angelic praise. His version invited singers to lift their voices alongside the herald refrain.

This change allowed worshippers to personally participate in the Biblical narrative. No longer were we just overhearing the angels. Whitefield’s lyrical tweak let us raise our own hallelujahs to the “newborn king,” magnifying the miracle of Emmanuel, “God with us.” The adjusted vantage point from earth to heaven amplified the revelation.

Both Charles and John Wesley likely would have opposed the rewrite, as the brothers discouraged editing their meticulously crafted hymns. Yet Whitefield managed to retain the substance while injecting vigor fitting of the joyful subject. His inspired edit married exuberant tone with solid theology—a potent combination.

The carol was one step closer to the cherished Christmas standard we know today.